State of the Union: Wellness

At the top of the year, I wrote an essay called “How Should Wellness Be?” In it, I attempted to tap into the reasons for my interest in wellness — and to reconcile wellness’s many faces: wellness as a cultural phenomenon, as an industry, and as a legitimate and earnest pursuit.

In that essay, I laid out my personal arc toward wellness. It’s a story that likely struck many of you as familiar. At least, it’s one I’ve heard reflected back to me several times. It goes like this:

Girl raised on Western cocktail of generous antibiotics and birth control starts noticing slight maladies; girl seeks help from conventional American doctors but gets prescribed more antibiotics, more pharmaceuticals; girl turns away from medical industrial complex to heal naturally; girl finds herself, like Carroll’s Alice, in the land of wellness, rife with whole foods, alternative therapies, and slight skepticism.

Since then, I’ve been ruminating on what wellness means to our culture. It seems to be symptomatic of the modern condition that simply feeling well is now something that a growing number of us go out of our way to do. It also seems that those of us who want to feel better have found no easy footpath, but rather an ever-shifting mirage in which the meanings of what it means to feel good & live well change by the day.

As Katie Stone wrote last week in her newsletter Plant Based, “the term ‘wellness’ has lost its true meaning. Wellness is now an industry riddled with unnecessary (but sometimes wonderful) products like probiotic face washes and sauna blankets.” Perhaps the term wellness has lost its meaning not solely because of the way commercial capital has infused the space, but because the pursuit of wellness has become so popular as to take on a million and one meanings. Wellness has clawed its way out of the fringes and into the mainstream. And so the issue is not only that wellness has lost its meaning, but that its meaning is increasingly manifold. Wellness is an earnest pursuit, but it’s also an industry that has capitalized on that very fact.

What Wellness Has to Do With Politics

This is related to politics but is not politics entirely: our sitting president won the oval office in large part thanks to RFK Jr., one of the most popular third party candidates of all time. RFK Jr.’s ascendancy was largely bolstered by the millions of Americans, myself included, who might not wholly agree with RFK Jr. but nevertheless feel strongly about the implication of “Make America Healthy Again” — that our country is chronically sick, and not by the fault of its people. America is unhealthy because of greed — greed of pharmaceutical companies, of food corporations, of some tech companies, too. That distrust of the medical establishment and Big Food is sometimes interpreted as something of a right-wing dog whistle astounds me, seeing as the calling out of corporate greed should, theoretically, transcend party lines.

And yet politics is an industry of its own, too. Two recent events centered on MAHA crystallize this phenomenon:

The Big Soda Meltdown: SNAP currently gives about $5 billion each year to Big Soda under the umbrella of “nutrition” dollars for sodas & candies made out of ingredients that are banned in most other countries. In light of 20 states seeking to remove soda and candy from SNAP programs, big soda corporations tapped MAHA-aligned influencers through the marketing agency “Influenceable” to publish content tainting the push. Without disclosing that they were getting paid by Big Soda, these influencers decried government overreach and shared the same photo of Trump drinking a diet coke.

Meanwhile, Poppi soda, which began as an apple cider vinegar drink at a farmer’s market, sold to Pepsi for 1.95 billion dollars.

RFK Jr.’s declaration of antisemitism as a key health concern: “Anti-Semitism—like racism—is a spiritual and moral malady that sickens societies and kills people with lethalities comparable to history’s most deadly plagues,” he wrote on X, linking to a Health and Human Services press release about the U.S. government retaliating against Columbia University for pro-Palestinian protests. The university’s $51.4 million in federal contracts and $5 billion in federal grant commitments are now in limbo because it allowed its students to stand up against genocide.

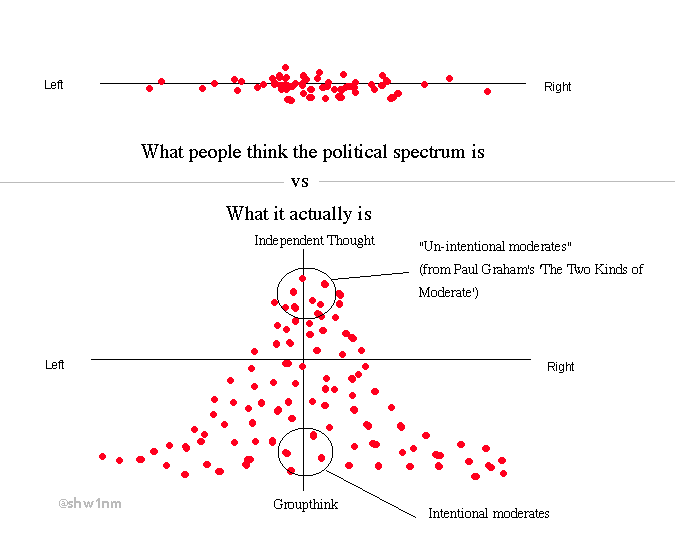

As a rule, I avoid speaking and writing about politics with people I hardly know. For one, people get touchy when beliefs don’t align. The below graph, from an article titled “Why I don’t talk about politics with friends,” illustrates my second reasoning: it’s difficult to resist the impulse toward tribalism, for propping up one political party or the other.

But I bring up politics for this reason: for a long time, health and wellness were two separate pursuits. For a long time, wellness was considered by most as a crunchy, perhaps cute, but ineffective diversion for real health (which was the domain of the medical establishment). Something has shifted in the past few years, thanks to people like Andrew Huberman and Mark Hyman and Hani Vari and even RFK Jr. The chasm between the medical establishment and the wellness movement — with its push for simple, non-chemical ingredients and independence from pharmaceutical dependence — seems to be shrinking by the day. Perhaps health really is that simple, the narrowing gap suggests: it’s just good ingredients, clean water, and clean air.

It’s become increasingly untenable to even think about wellness — as anything other than the pursuit of wellbeing — without thinking about politics and without thinking about corporations, huge forces of power that actually have the capability to clean up our water, make medicine more humane, and get the poison out of our food. For the first time in a long time, this might actually be possible. But of course, now that wellness is in the realm of politics, it’s more susceptible to being bought out.

Beyond Politics: Wellness as Personal or Collective?

I’m not writing to say something about politics; I’m equally distrustful of both political parties. I’m writing to say that the way in which wellness has infiltrated politics signals that the obvious and unequivocal ascendance of health and wellness culture.1

As it ascends, I’m taking fresh stock of what wellness means and how it iterates. I question if it’s still possible for wellness to be, solely, a personal endeavor, or if the nature of the enterprise now is necessarily collective.

For me, wellness has historically meant this: I go to sleep early and rise early. I spend as little time as possible on my phone, and I try to get sunlight, laugh, cultivate a sense of awe, nourish my mind, and take deep breaths. I move my body. I write. I pray. I don’t drink a lot of caffeine, and I take care to ensure that when I do, it’s clean caffeine — not laced with common contaminants like pesticides or mold. That is to say: I care about ingredients. I don’t drink a lot of alcohol. I try to eat seasonally and locally. I try to learn as much about how my body works as I can so that I can take care of it until it doesn’t anymore.

A couple of days ago, I wrote in my journal, “I’m trying to create a blueprint of wellness societally. I’m trying to map it as if is a building, a structure. I’m trying to take an X-Ray of wellness in 2025, to preserve it in time.” I drew a chart that I called the Wheel of Wellness. It looked like this:

This chart is inconclusive, just a doodle of initial thoughts. I would love to know: how do you think about the word wellness — either as someone who has bought into it or has not? Either way, I would love to know how you’re thinking about this phenomenon in the comments or in a message — if you’re thinking about it at all. ✦˚*

As of March 2025, the U.S. wellness economy reached a valuation of $2 trillion, accounting for nearly one-third of the global wellness market, in the middle on the level of the hundreds of restaurants that have eliminated seed oils; at the micro-level, like health and wellness trending and people like Dr. Mark Hyman and Vani Hari, aka The Food Babe, accruing more than 5 million followers combined on Instagram.