Last year, I stood in a spice grove in Goa, India. A slight, spindly man — the owner of the farm — stood before me and gestured to vanilla, nutmeg , mace, cardamom, and pepper growing around us: in trees, on vines, and in the ground.

“In other countries, you have the gluten allergy, the dairy allergy, the soy allergy, the nut allergy…” he trailed on. “In India, you don’t see that. We Indians eat up to twelve different spices in almost every meal. That’s twelve different plants.”

He went on to describe the medicinal benefits of each of his plants: vanilla’s antioxidant and serotonin-boosting superpowers, nutmeg’s ability to prevent cellular damage, piperine from black pepper’s aid in digestion and gut protection.

His words articulated what I have always felt about Indian food but never quite understood: India’s fundamentally maximalist approach to food. Not only do most Indian dishes contain a multitude of spices, but most Indian meals contain a multitude of dishes. Thali, a classic Indian lunch, is comprised of one plate with a dozen of various dishes stacked upon it. But perhaps one of the most common Indian staples that utilizes a profusion of spices is the ubiquitous chai, or tea.

Chai exhibits the classic Indian proclivity for jamming dozens of power-packed, rich spices into one dish. And yet chai is a relatively new phenomenon in India, given the grand scheme of history.

Despite the fact that masala chai has become nearly metonymic for India, at the beginning of the twentieth century the majority of Indians did not know how to make a cup of tea and were not interested in learning how.1 This is astounding given that India and Sri Lanka are now some of the world’s largest producers and importers of tea. How did this happen?

Where Did Tea Come From?

Tea-drinking originated in China in the 4th century, then gradually spread to Japan. Eventually, tea leaves spread to Northern India, in places like Assam, but were primarily chewed, not steeped. When the Mughals invaded India, they brought coffee, but that didn’t really catch on.

Meanwhile, in Britain, tea-drinking was all the rage. So much so that by the 1830s, the average Brit was drinking a pound of tea every year.2 For a long time, Britain imported their tea from China because they had a trade monopoly there. But starting in the 1830s, that trade monopoly was falling apart.

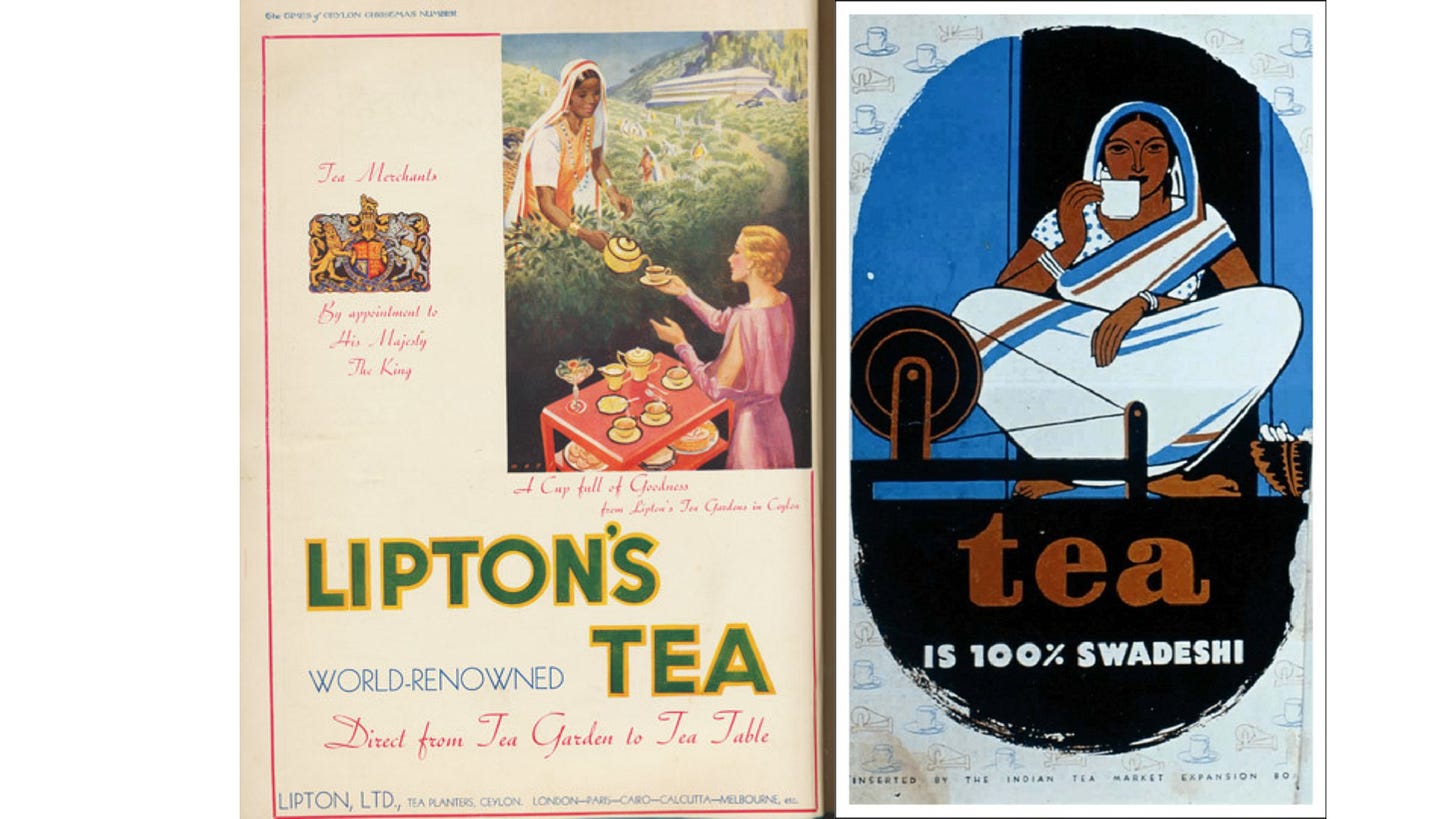

The colonists eyed India as their new source of tea. They launched a full-scale campaign to make India = tea, trotting around their Indian tea at those ubiquitous “world’s fairs” — i.e. colonization fairs — of the late 1800s.

It worked. In the 1800s, 90% of Britain’s tea came from China. By the early twentieth century, 83% of Britain’s tea was grown in South Asia.

India Reclaims Tea

Before the British, Indians considered tea little more than medicine for acute pains: colds, chest unease, and the like. A man from Mirpur recalled his first time drinking tea: “The first time I had a cup of tea was when I came to Bombay. In the village we used to drink only milk, and water. Only if somebody was ill they would give… something like a cup of tea—it was like a medicine.”3 Even after tea’s initial foray into the South Asian subcontinent, Indians still regarded the beverage with suspicion and hesitation.

But then British-owned India Tea Association launched a massive marketing campaign in the early 1930s to spread tea across India. Britishers traveled town to town, house to house, showing Indians how to brew a cup of tea. Like traveling salesmen, they set up shop in courtyards and villages, conducting demonstrations of how to make tea. Eventually, with the advent of World War 1 and the Industrial Revolution, tea eventually began to catch on as a salve for a labor-intensive lifestyle.

But then something interesting happened: Indians made tea their own, simply by adding their own indigenous spices. The British rebuffed this “spiced tea” because it meant that India, now their largest market demographic, used fewer tea leaves and more spices to brew what would become the de facto drink of India.

“Spiced tea,” now known as chai or sometimes masala chai, outperformed Britain’s more plain counterpart. And then, around the time that India sought independence from Britain, it launched its own marketing campaign to reclaim tea as uniquely Indian, not British. And it was — at that point, tea was produced in India by Indians and steeped with indigenous Indian spices. By the time that India achieved its independence, the country had successfully rebranded tea as its own.

Masala chai emerges as a hybrid beverage, brewed in the throes of colonization and reclaimed in the days of Independence. Chai combines the British persuasion of tea with the ancient Ayurvedic tradition of boiling water with honey, ghee, black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon and other spices to fend off fevers and colds.

The more I write about wellness practices that appear to emerge from specific cultures — yoga, chai, et cetera— the more I sense that the cultural practices that are often assumed to be monocultural or ethnically “authentic” are almost always composite practices, the results of cultural contact and, of course, conquest. Chai is a perfect example of this.

If you’ve read my work for a while now, you probably know that I’m not interested in moralizing the past. What I am interested in is understanding how disparate historical streams join together and form new pathways, eventually becoming inextricable — and seemingly unremarkable — parts of the landscape.

Plus, in addition to its history lessons, as one writer put it in 1941,

“Psychologically tea breeds contentment. It is so bound up with fellowship and the home and pleasant memories that its results are also magic.”4

The Perfect Chai

It’s important to note that Indians make chai in one million and one ways, depending on geography and taste. There is no definitive recipe for chai. But there are patterns, common threads, and of course suggestions (mine below).

Here’s a non-comprehensive rolodex of the various spices that Indians — from all over the subcontinent — steep to make chai, as well as their medicinal benefits:

cardamom: also known as the “queen of spices,” cardamom is rich in polyphenols, anti-inflammatory, and pro-metabolic

fresh ginger: ginger comes from the same plant family as turmeric and cardamom. Its roots are super high in antioxidants, surpassed only by pomegranates and certain kinds of berries

lemongrass: originally from Sri Lanka and South India, lemongrass has been used by villagers for centuries as an antiseptic, antidiarrheal, and antibacterial tonic.

mint: a lesser-used chai ingredient, mint is a fantastic way to add a twist to your chai and benefit from its abundant benefits, such as prevention from cancer development and anti-obesity, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and cardioprotective effects.

clove: again, very high in antioxidants — there’s a pattern here. The reason why antioxidants are so key is because they help our cells fight free radicals, which lead to inflammation and premature aging. Consuming clove lowers inflammation, pain, fungus overgrowth, and so much more. I once put whole cloves in my mouth to alleviate the pain of a tooth infection; the craziest part was that it worked.

saffron: the research coming out about the power of saffron to alleviate mood disorders is actually astounding. Saffron, which is actually the pistil of a purple flower, not only imparts a lovely, subtle floral taste but also boosts my mood and calms me down.

star anise: star anise is said to be antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, gastroprotective; providing relief from coughs, respiratory congestion, migraines, skin infections; it’s said to be an aphrodisiac, too.

black tea: lastly, the star of the show herself. Black tea is not only a carrier of medicinal herbs, but is also medicinal in its own right. It can lower your risk of heart disease, and other studies have shown that the theaflavins in black tea are just as potent antioxidants as the catechins in green tea (i.e. the EGCG in matcha).

While the health benefits of traditional chai ingredients are incredible, making the perfect cup of chai need not involve so many spices. When I start a pot of tea, I use just three:

black tea

copious amounts of ginger, more than you think you’ll need

green cardamom pods, broken open with my fingers or smashed to reveal the seeds

Add all to a pot on the stove with water, bring to a boil, and add milk at the end until your tea reaches the desired hue.✦˚*

E.M. Collingham, Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, p. 188

Collingham, p. 192

Caroline Adams, Across Seven Seas and Thirteen Rivers, p. 182

Christina Hardyment, Slice of Life: The British Way of Eating Since 1945, p. 5

I'm so glad our time in Goa has found it's way into your work. What an incredible time we had on that farm. Still thinking about the honeycomb that sweet man pulled out that was shaped like a heart <3