There are two camps when it comes to yoga. First, there are those who step into a yoga studio, press their palms together, and whisper words like namaste, fully bought in to the idea that they are partaking in a 10,000 year old tradition revealed by ancient Vedic sages and passed down the line to them.

Then there are those, less common, who regard yoga as an invention, a mangled thing, dating back about a hundred years ago during the colonial period and then exported wholesale transnationally.

The truth of course is somewhere in between: the Rig Veda and Upanishads, some of ancient India’s seminal spiritual texts, of course speak of yoga. For thousands of years, from the Vedas on, yoga was passed like a baton between these guys:

But for most of yoga’s lifespan, the practice was mostly a path toward self-realization, not an exercise or movement. If yoga is now known to the modern world as a practice of breathing and posture exercises, it wasn’t always this way: for centuries, yoga was solely a spiritual practice, one that entailed unsexy and unpleasant things like ethical restraints and observances (yama and niyama), breath control (prāṇāyāma) and retention (kumbhaka), bodily seals (mudrā) and binds (bandha), and meditation techniques (dhyāna).

If yoga had stayed in its proverbial lane — that of the spirit world — without veering into the physical, it is likely that we in the West would know nothing of yoga at all: there would be no yoga retreats in Costa Rica, no $130 Alo yoga pants. Without a physical form, it seems unlikely that yoga, which has since become a 22 billion dollar industry in the U.S., would have so intensely sparked in the American mind.

When yoga was first exported to the Americas in the 1800s, it was packaged as a spiritual panacea. In a letter to his friend, transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau wrote, “I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”

Thoreau was perhaps the first self-described yogi of the West, where transcendentalism emerged, like yoga, as a malady for America’s spiritual hollowness, which surprisingly was a problem even then. Swami Vivekananda, the man most famous for popularizing yoga in the West, said, “As our country is poor in social virtues, so this country is lacking in spirituality. I give them spirituality and they give me money.”

One of Vivekananda’s disciples, an American woman named Laura Glenn, predicted that India would soon become a haven for spiritual formation. “As students in the past have gone to Paris to study art and to Germany to study music, so they will in time turn to India to acquire… the most efficient method of developing the religious consciousness,” she wrote in her diary. Glenn eventually fulfilled her own prophecy, traveling to India and taking the name Sister Devamata.

It turns out that this wasn’t really necessary, because the Indian spiritual missionaries were so successful, and you converts so satisfied, that there wasn’t really any need. It took a bit of rebranding: as Vivekananda admitted to a friend,

“You should know that religion of the type that obtains in our country does not go here. You must suit it to the tastes of the people. If you ask [Americans] to become Hindus, they will all give you a wide berth and hate you, as we do the Christian missionaries… but they will give you the go-by if you talk obscure mannerisms about sacred writings.”

The conditions that made 19th century Americans amenable to yoga, in my estimation, aren’t too distant from the reason why yoga is a multi-billion dollar industry today: the practice feeds — or purports to feed — a spiritual yearning that Americans are desperate to resolve.

If Westerners flocked to Indian stretching for its purported spiritual riches, it was because they actually craved the structure and meaning of a deeply religious society and felt adrift in the absence of a moral and metaphysical worldview. This was true 150 years ago, but it’s a trend that continues to this day. It reminds me of Carl Jung’s thoughts on yoga:

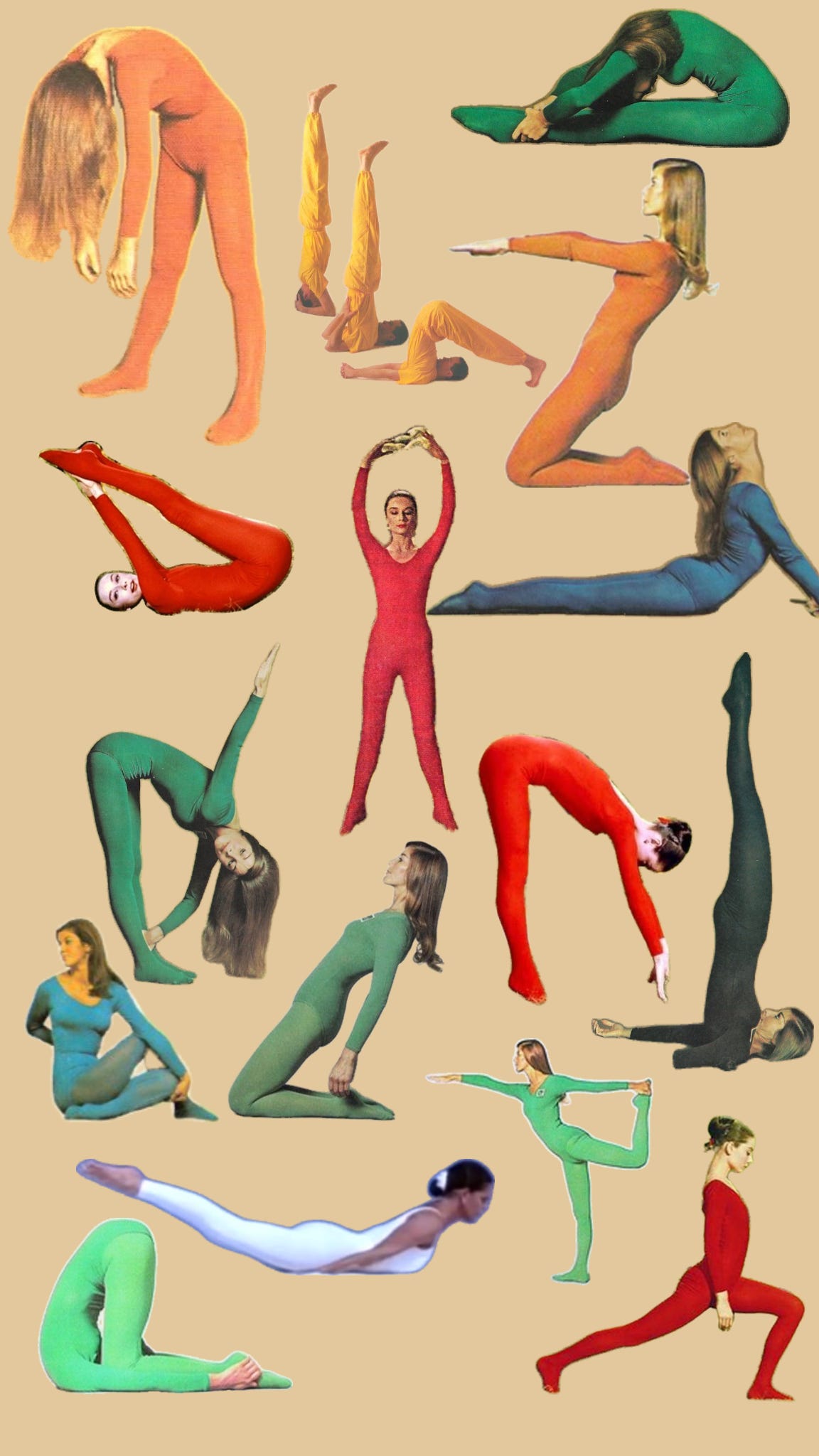

Jung’s critique, while harsh, scrapes up some bit of truth. He touches on a feeling that has overtaken me when I attend yoga, which I have intermittently for much of my adult life: that I am performing the motions, gesturing at some sense of wholeness or virtue that is forever hazy to me, just beyond my reach. I am aware that many people feel that yoga provides such spiritual fulfillment; I’ve just personally never been able to attain it in a yoga studio, sweating through polyester leggings and bending my limbs to resemble dogs, crows, moons, and trees.

Through all the sweating, the bending backwards and loosened joints and deep breaths and prayer hands, I wonder why spirituality must present itself in a different language for it to take in the United States. And what does it mean that millions of people can only access the spiritual realm — or their spiritual self — when uttering phrases from another culture whose language they don’t speak and whose customs they only vaguely understand?

There will always be detractors who push back: perhaps yoga is not that deep, perhaps it’s just exercise. But we all know that’s not entirely true. Yoga might bear the trappings of exercise, but is at its core a series of gestures toward something greater, something divine. That such gestures, in the United States, must be cloaked in the “obscure mannerisms” of another culture says something about our willingness, collectively, to look squarely at the face of what ails us, what scares us — which is another way of saying, at ourselves. ✦˚*

Note: This is the second installment of a longer series on the transnational histories of modern posture yoga. If you enjoy these conversations, consider subscribing (it’s free!). And please, drop me a comment if you can — I love to hear from you.