When I was twelve, my family was asked to leave a friend’s house when my mother insulted my friend’s mother. The subject of dispute? Yoga. Can Christians do yoga? This may seem a silly question to those who do not live and die by their belief. My mother, who was raised Hindu, argued that to partake in yoga is, fundamentally, to practice Hinduism. To her, this was not a pejorative statement, just a statement of belief. My friend’s mother said that, when she was in yoga class and oms or shantis were spoken, she would pray to Jesus instead.

Of course this would not have been an issue if my mother and her friend practiced Hinduism instead of Christianity, which mandates that God is singular and discrete. One cannot believe in the tenets of the New Testament and the Bhagavad Gita, because in the New Testament there is only one God, and that God lives in the Bible and nowhere else.

But I did not take this lesson as a child. Instead I saw two women, one white and one brown, adjudicating culture, deciding what belonged to whom.

My father descended the stairs of my friend’s house and informed me that we were leaving. I questioned our abrupt departure. But why? I asked. My father looked at me, the trace of an amused smile on his face. He was staying out of it. It was almost as if he viewed their spat as a girl thing, a cat fight. And perhaps, in some way, it was.

I grew up and tried yoga for myself. It wasn’t really for me, I decided, despite the fact yoga and I shared similar origins. I couldn’t help feeling like American yoga was made for people who don’t believe in God but secretly want to. As Joseph Alter writes, “Yoga has become something you believe in.”1

When writing about yoga, I kept returning to God, though I set out to write about culture. The more I wrote, the more I wondered if culture is nothing more than a set of beliefs — beliefs about the spirit world but also health, morality, and beauty.

In every yoga studio, I saw the symbol ॐ, heard the word namaste. In India, namaste is but a formal greeting — a how-do-you-do — but in the United States it is a spiritual sign-off, something that feels good for yogis to say. The light in me sees the light in you, the yoga teachers croon.

Rare are the Indians in these yoga classes. It would be easy to resent this — instinctual, even. The way that a cultural tradition has transformed into Alo yoga pants and low-toned injunctions to “let go of what no longer serves you,” reminders that I am “exactly where I am supposed to be.”

But I don’t resent this. Here’s Swami Vivekananda, the man often credited as bringing yoga to the West: “As the different streams having their sources in different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee.”

Vivekananda actually looked down on asanas — the physical facets of yoga, preferring to dwell instead on its mental and spiritual benefits. Yoga, a Sanskrit word meaning union, was a cosmic goal for Vivekananda.

Here he is again: “All differences in this world are of degree, and not of kind, because oneness is the secret of everything.”

I was raised by one Indian parent and one American parent, in a family without the slightest sense of cultural ownership. I have seen my father roll chapatis as he would a taco and mix horseradish into his basmati rice. We belong to one another, not to some idea of cultural purity.

We adapt to one another, too.

It’s not just yoga: bindis, lehengas, haldi doodh, golden milk, bangles, henna, Om (ॐ). These constitute “culture” but also belief and fashions, signs of the times. In the West, we argue over them, like a tug of war.

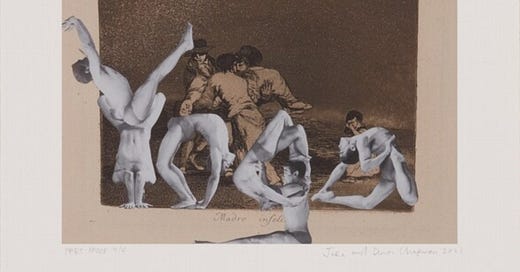

It is said that Krishnamacharya, the real father of modern posture yoga — also known as asanas — developed the practice by melding traditional yoga poses with Western gymnastics and British calisthenics. It is for this reason, as well as many others, that Indian historian Meera Nanda invites us to “enjoy the mongrel that this thing called modern yoga is.”

Recall that Old Testament story, in which two women beseech the king of Israel to decide the fate of a baby, who both of the women maintain is their own. Upon seeing the child, the king orders the court to cut the body of the living child in two, at which point, the baby’s true mother cries, “please, give her the baby! Don’t kill him!” The false mother, on the other hand, was ready to allow the execution of the child she had, just moments before, called her own.

The moral being that true love does not seek to possess.

Eventually, my mother and her friend patched things up. There were flowers and crying involved. Hugs. And a useful lesson for me: yoga is not just yoga. Yoga has multiple meanings. And, as Vivekananda says: “truth can be stated in a thousand different ways.”

I have become a social yogi; that is, I practice yoga socially, as one might drink “socially.” Frequency: four times a year. For the most part, I have other ways of sharpening my core and connecting with God.

But when I do find myself in the studio, I find it useful: to stretch, and to create a mental catalogue of the phenomenon that is American yoga. In downward dog, I see sweat dripping on mats and spandex clinging onto thighs. I see a light-up ॐ glowing on the back wall. I consider how it is this very characteristic of yoga — its hybridity — that allowed it to reach such grand proportions in the West.✦˚*

Note: This is the first installment of a longer series on the transnational histories of modern posture yoga. If you enjoy these conversations, consider subscribing (it’s free!). And please, drop me a comment if you can — I love to hear from you.

Joseph S. Alter, Yoga in Modern India, pg. 13.

My mother also had a serious Christian friend who refused to practice yoga! Looking forward to this series.